There has never been a woman president of Cuba nor has a woman come close to being an eligible candidate. While other Latin American countries have broken through this “glass ceiling” with women who became the president of their country (Violeta Barrios in Nicaragua, Mireya Moscoso in Panama, Michelle Bachelet in Chile, Dilma Roussef in Brazil, and Cristina Fernández in Argentina) during the last decades, Cuba cannot be listed among this advanced group. Women’s right to vote was approved on the island in 1934, and it was not until two years later that women were able to vote for the first time.

It should be noted that, in the history of the continent, women never staged a coup d’etat nor set out to maintain absolute power for an unlimited amount of time. The ones we mentioned, all reached the highest seat through elections. The history of the island, on the contrary, has followed a very macho line of development, from which it has never succeeded in breaking away, including – or to an even greater extent – in the period of the Revolution that began in 1959. They have been only men, and so few that they can be counted on the fingers of one hand – and with a finger to spare – those that have ruled the island for more than half a century, can be summed up in two brothers of the same surname.

All this time, the upholding and reproduction of power, as far as its ideological basis has proceeded through a reaffirmation of patriarchal leadership, wrapped up in a cult of personality and an epic speech that dispensed with the female figure as the subject of political changes. This masculinization of national life was also based on the model of the supreme leader, devoid of a public visibility for the wife or the rest of his family, with the same paternalistic pretext with which the idea of a woman was reduced in general to a passive object of power, established as a beneficiary or someone to be assisted, through measures such as the legalization of abortion, and the massive incorporation of women into areas of studying and work (demands that were added to the traditional slavery in the domestic sphere).

In 2009, the feminist movement was continuing to knock on Cuba’s doors, where gender approaches were still confined to academia and literary studies, to the point that Raúl Castro himself had to realize that women did not have enough of a presence in public offices, when he said at a women’s congress: “It is a shame that after 50 years of revolution, with all the progress that we have made on so many issues […],only a few female leaders have emerged in the different areas.” In that year, women occupied 27% of the parliamentary seats in the country (including the assemblies at the municipal, provincial and national levels), despite constituting half of the population. The percentage was going to change in the years ahead, taking dramatic leaps (already by 2010, women held 33% of these seats, and by 2013, the percent reached 48.86%, which put the country in first place in Latin America and fourth in the world.) Therefore, it is worth asking how life has continued to function in light of such figures and if there was a real change in the mental and social structures, over such a short period of time, if an advance of feminism had taken place, or if we are only dealing with the result of another measure taken from above.

Evidently, the centralism of power has merely brought about new statistics rather than a positive change in reality, by not allowing for the logical development of civil society and feminist action. Manuel E. Yepe, an official journalist from the state media, acknowledged that it was “necessary to reinforce the revolutionary political will to correct such stubbornness” (Cubadebate, February 16, 2013). In practice, it was not necessary to create a quota or law about gender parity, because in Cuba the vertical power of the state was capable of imposing the norm for women to benefit from these different positions, sometimes even forcing their own willingness. Now, do these female leaders have a gender perspective, or have they come to reproduce the same type of patriarchal power? In this regard, says professor and feminist Teresa Diaz Canals: “Due to the excessive politicization of the life of the feminine social movement, this gender approach is not present in politics at all. […] Our female leaders are replicating a discourse that is patriarchal, pro-government and top-down that cannot really reach the heart of our society.”

Among those who address the issue of gender in Cuba there is a play on words, from the dominant concept “Marxism-Leninism”, to name the new type of patriarchy imposed during the period of socialism and that corresponds to the top-down superstructure of the state, which is autocratic in nature and excludes individual initiative, and which reproduces an androcentric model. It is called “Machismo-Leninism”, and it starts from the formation at an early age, when girls and boys without exception have to exclaim a motto before entering the classrooms: “We will be like Che”. Multiple generations grew up under a series of obligations that have sought to bring about the homogeneity of the population, in accordance with ideological patterns that reinforced macho behavior and gender stereotypes.

With few or no possibilities of feminist activism and women groups that have emerged from below in an authentic manner, the figure of state power reserves the right to occupy that void created by the legal and institutional apparatus itself. This view has been affirmed by the researcher Liudmila Morales Alfonso: “… without feminism, the gender dimension of many social problems that today constitute concerns in Cuba is diluted. Thus, a vacuum is created, which is occupied by the State as the universal guarantor of rights. And with it and its masculinist character, the absence can become a structure for the reproduction of power relations and for the naturalization of inequalities that move the debate away from an understanding of social relations, in terms of gender” (Socialism and Feminism in Cuba: Does it Add Up to Equality or a Call for Differentiation? Cuba Posible).

Under these conditions, some of the main problems are systematically hidden or denied. Cuba may be the only country in America where there are no statistics on femicides, nor are there any systems in place for the monitoring of gender violence. Even Mariela Castro, Raúl Castro’s daughter, and director of the National Center of Sexual Education of Cuba (CENESEX) has come forward to claim that: “We do not have, for example, femicides. Because Cuba is not a violent country, and that is an effect of the revolution “(Tiempo Argentino, November 4, 2015). The most urgent problems, such as the undeniable cases of femicides, meanwhile, have to emerge only by alternative means, through illegal independent journalism and social networks on the Internet.

However, we have seen that, based on internal and international social pressure, the ruling party has begun to adopt language and approaches inherent to feminism as a state discourse, while it relies on statistics that show the growing presence of women in public office. This, beyond the formalism of certain data, serves in practice to hide the limitations suffered by the Cuban woman in a society marked by poverty, the lack of civil liberties and a macho culture that constitutes the relations of dependence towards men, and an environment made worse by the submission of women to the figure of the State-male-provider.

I am in agreement with the Italian feminist Silvia Federicci in that it is correct to always distrust state feminism, and – I would add – that there is that much more reason for this distrust when it is a society restricted by what the same theory has defined as the “systemic machismo” of Marxist ideology: “But we have verified that women who are integrated into the State, who do politics […] do not change the policy of the State […] They only give us the illusion that something has happened […] That is why I have no confidence in the women who are from the State, I only have confidence in women who are building from below, based on new forms of organization.”

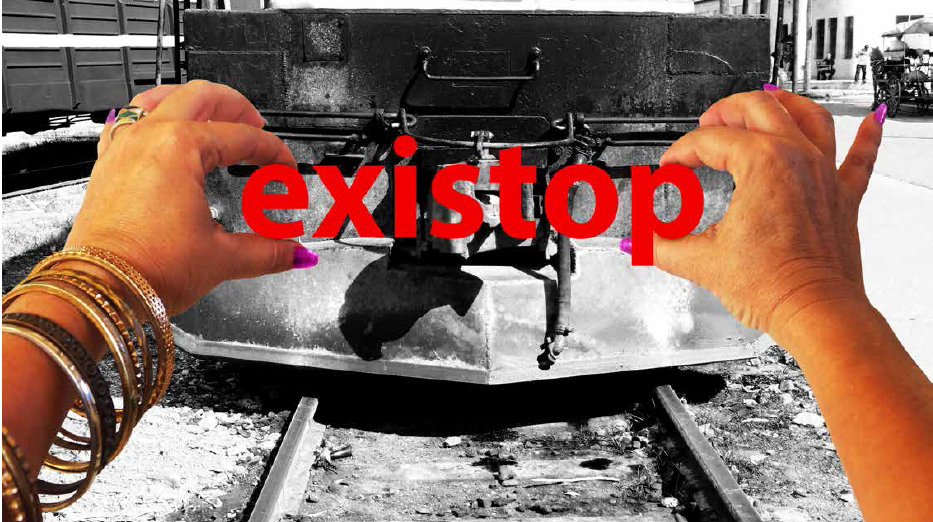

When Cuban artist Tania Bruguera gave a performance in 2016, recorded on video, about supposedly running for president of Cuba, she came to take down many “Machismo Leninist” stereotypes. She opened, among others, a question: will it finally be possible to imagine a woman as president in Cuba? This mock self-nomination took place in the context of the race between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump for the White House. In addition, Raúl Castro had announced his retirement, hence the probable end of the era of this surname in power was approaching, at least formally, something unprecedented for several generations on the island. Bruguera explained: “People should be able to have this fantasy of another political system.”

We could ask ourselves if Cuban society is capable – and if its women are – in the current context, to elaborate on this “other” fantasy in which a woman occupies the presidency of the country. Are we at least entering the point where it is imaginable? No woman has been tossed out among the possible names to replace Raúl Castro, nor has one been able to become a symbolic capital in a society – all within an electoral system where neither political parties nor political programs are allowed, where both male and female leaders, when they arise spontaneously and promote profound changes, are much more likely to go to prison or into exile than to hold public office.

Perhaps the most interesting question posed to the conscience of the men and women of Cuba, would not be if a woman might hold the role of maximum representative of power tomorrow, something that should seem as possible as any other unexpected plan – there are currently two female vice presidents-, but whether that Cuban woman could be found acting right now on behalf of those below her and with a true gender perspective.

More difficult than assigning a woman to fulfill the role of this fantasy, lifting her up to the presidency, would be to realize that gender equity and the disappearance of any type of violence or discrimination against women could be achieved democratically, along with other human rights. Without such achievements, is it possible to imagine a nation with true democracy?

Leave a comment