Back in the early 1960s, Cubans were given an opportunity (perhaps by mistake) to watch the latest films directed by Luis Buñuel (1900-1983), which were shown in the cinemas of Havana. Yet, as soon as the authorities of the Castro regime realized the “evil” nature of the scenes and the dialogues, the films were banned for good.

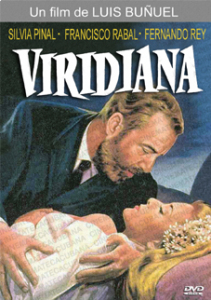

At the same time in Spain, Buñuel faced expulsion (a second one already) from Madrid ordered by Francisco Franco, despite being recognized worldwide as a genius of the seventh art. He was banished just after Viridiana had been released – a film which inspired awe and caused bewilderment among all the cowardly followers of the Spanish dictator.

Seemingly, the attitudes of the Maximum Leader of the Cuban Revolution resembled those of his Spanish counterpart. Indeed, there were even rumours that the two dictators felt sympathy for each other.

Living outside his homeland from 1937, Buñuel returned to Spain – with Franco’s permission – thirty years after the start of his career with the intention to shoot Viridiana in a beautiful estate on the outskirts of Madrid.

In 1961, the movie was shown in Spain and in many other countries and was awarded the Palme d’Or, the highest prize of the Festival of Cannes, where it represented Spain.

However, Viridiana was a film that surprised, annoyed and/or confused everyone, as if it was a kind of Buñuel’s hidden letter. Many people came out against it; among them, naturally, Franco, the Vatican and anyone opposed to the fundamental values of a modern, open democratic society.

Buñuel’s rich, fabulous imagination, which was now more mature and drew on wider experience, revealed, with an incredible degree of venom and lucidity, a world in which we all have our share of fault. Viridiana develops the concept of crucifixion of a rebel – or rather, a self-styled rebel, who, despite everything, is in control, holding the reins of power in this world in which self-esteem and ability to take care of oneself are essential qualities that can only be achieved by perseverance, persistence and a positive attitude to life.

Neither Franco nor Castro liked the fact that the films of Buñuel, filmmaker from the Spanish province of Aragon, reflected anti-dogmatic attitudes. Nor did any of the two welcome that his films, tinged with the chords of Haëndel’s Hallelujah and Mozart’s Requiem, showed the advance of the kingdom of capital and the decline of the kingdom of religion.

Thus, neither dictators nor autocratic rulers considered Viridiana a good example to follow as it clearly shows the consequences of repression. The film’s heroine, Viridiana, lives a life that can be best described as that of absolute purity, night prayers and flagellation; on the other hand, there are enough resources to develop the estate which she co-owns with her cousin Jaime and make it thrive.

Viridiana is a movie full of symbolism, a provocative, audacious and thought-provoking work of art of Luis Buñuel, a clear-thinking artist with great knowledge of human psychology, in particular, of the psychology of the masses, who dared raise a powerful warning voice against the harm caused by obsolete political and religious ideologies.

The end of the movie could be seen as a hard lesson for politicians which count on support of the lowest classes: the novice Viridiana, the protagonist, brings all the needy people of the town to her lavish mansion and seats them at a table resembling in style Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper. She lets the women and men eat and drink anything they want and when they are all full and get drunk with good wine, their second face emerges: they betray Viridiana, destroy everything in the house, rob her and even try to rape her.

A scene that Fidel Castro could hardly admit or bear to see.

Leave a comment