Five days after the announcement of Fidel’s death, an atmosphere of grief and mourning could be felt both in Havana and in any other part of the country. The six national TV channels successively transmitted and retransmitted programmes about the “Maximum Leader”, the “Father of the Revolution”, while the body of the deceased was travelling back in a caravan to Santiago, where it would be laid for eternal rest.

The overall mood that this singular event evoked in people in the streets could be best described as that of “uncertainty” and “consternation”. No one really wants to talk about it. Yet, I insisted and asked one of the cooks from the Círculo Social Los Marinos community centre who used to say that when Fidel dies, everything will change. I wondered what are his views now. Pressed for an answer, he made a brief comment: “Nothing. Nothing has changed. Things could perhaps only get worse.”

Unpublished images along with others that we have seen so many times keep reminding us of the attitudes of the man who is going to rest next to José Martí. As it seems, he not only managed to position himself as the protagonist of the nation for fifty-eight years, he’s now threatening to become national heritage.

85-year-old Eliades, retired from the field of commerce, says that the news just won’t let him rest: “I have heard about Fidel’s death so many times that now, when it’s real, it suddenly seems hard to digest. I feel as if he was hidden somewhere, watching everything, listening to what people say and what they say… only to take action later.”

Fayula is blind. He sells jam on the street. Carrying out illegal trade earns him just enough to fill his box of food, buy his cigars and play lottery on a regular basis (the lottery known as la bolita held in Miami, which is illegal in Cuba). If any of his numbers wins, he’ll be able to take a break from walking the streets in the sun and chanting his offer of the day, finding his way with a cane and paying attention to the signs of good luck that life brings to him.

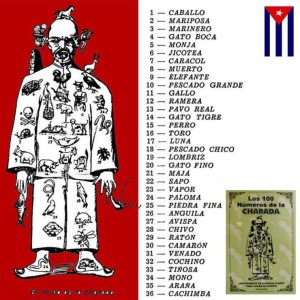

I asked Fayula about the Commander’s death. He told me: “It’s really something, you see. Imagine that just one day after his death he ruined all the banks where the la bolita lottery was held. The numbers drawn in the night of his death were ninety (his age), twenty-five (the day of his death) and twenty-six (the year in which he was born). That’s why many people won. What do you think? The numbers drawn yesterday were one, which is the horse (Fidel’s nickname), eighty-eight (the great dead), and ninety-three (the Revolution). Once again, the banks had to borrow to be able to pay prize money to the winners.”

The la bolita lottery is prohibited in Cuba. Betting on numbers in this lottery is a crime that has put thousands of bankers and tipsters in prison throughout the years of socialism. There’s no doubt that playing lottery is a valve of escape to alleviate the economic crisis that the country has been going through for decades. A bet on a winning number is certainly an aid to the inadequate official salary.

Moreover, the tradition of the lottery is firmly rooted in the depth of Cuba. Neither the laws of the Revolution nor the repression have been able to eradicate it. Recently it has seen a major revival – it’s been so marked that it seems that the lottery is currently hovering on the edge of the permissible. Fayula says: “Who knows, playing the lottery might not be so severely persecuted without Fidel; maybe it won’t be seen as reprehensible anymore. One day it might even become a kind of social entertainment, a game played for distraction like in other countries. Besides, the State also earns profits from it, not only individuals. I hope that people in Cuba will be able to play la bolita again, freely, along with many other things.”

Leave a comment